Creative Ageing ZUTTOBI is a project organized and operated by the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum and Tokyo University of the Arts. The term ‘Creative Ageing’ considers what it means to grow older creatively and encourages a positive perspective on aging. The name Zuttobi combines ‘Tobi,’ the abbreviation for the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum, with ‘Zutto,’ meaning ‘always’ or ‘for life’ in Japanese. The initiative aims to create a society where art and museums remain accessible throughout one’s life. This initiative involves interdisciplinary research and practical applications in collaboration with Tokyo University of the Arts. We interviewed four people involved in Zuttobi, and the story is presented in two parts.

Exploring a Way to Formulate the Program

Inaniwa: Thank you for being here today. Could we start with introductions?

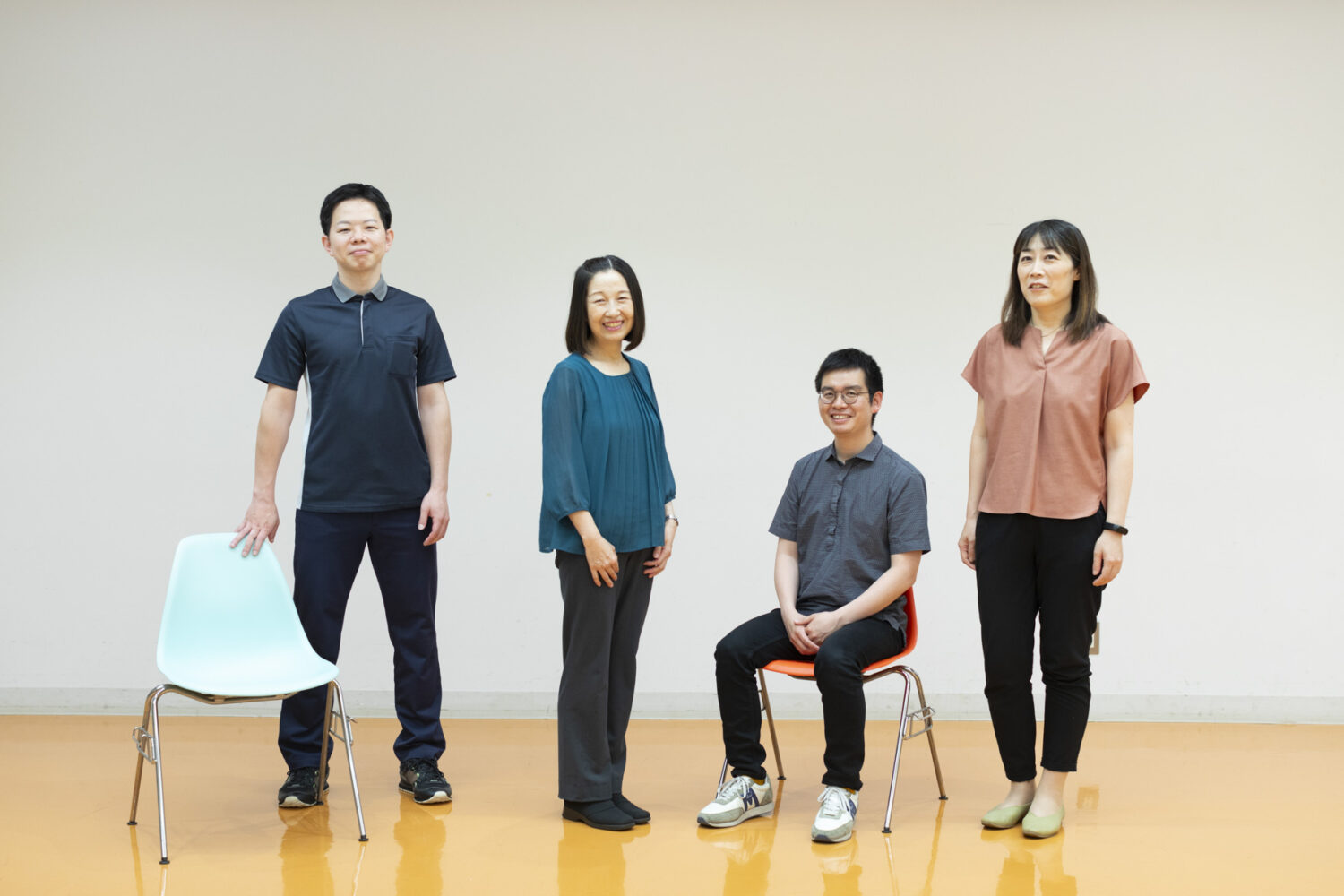

Kanahama: My name is Yoko Kanahama from Tokyo University of the Arts, also known as ’Geidai’. I work as the Program Officer for Creative Ageing ZUTTOBI. In addition to existing museum activities, I develop programs that create opportunities for older adults to engage more actively and creatively with the museum.

Fujioka: I’m Hayato Fujioka, a curator at the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum (Tobikan). Alongside Ms. Kanahama, I work on implementing and researching programs in collaboration with medical and welfare professionals. We aim to increase opportunities for social participation through the museum’s artworks and architecture, creating a variety of opportunities for connection and communication for not only active older adults but also for art enthusiasts who feel distanced from museums due to physical barriers.

Chigasaki: My name is Yoshiko Chigasaki and I’m from the Taito Council of Social Welfare where I work as a Community Social Worker. Community Social Workers coordinate efforts to establish systems where multiple generations in the community can support one another.We listen to local residents, identify challenges, and work out what we can do to tackle them.

Nomoto: I’m Junya Nomoto, a Registered Occupational Therapist at Taito Hospital. Generally, registered occupational therapists are responsible for rehabilitation. In my department, we work with people not only within the hospital but also with the local community. For example, since 2017, we have hosted a dementia café called “Café YOU” in the hospital lobby. It was during one of these events that members from the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum, including Mr. Fujioka, visited us, and we were able to establish a connection with the world of art.

Inaniwa: Activities that link art and culture with health have really only just begun here in Japan. In the UK, a forerunner in this area, these activities are now referred to as “Creative Health” and are becoming more widespread and community centered. Could you please tell us how healthcare, social welfare, and the Museum work together here in Tokyo’s Taito district, where the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum is located?

Fujioka: The connection between the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum and local welfare and healthcare began around 2019. At that time, you, Ms. Inaniwa, were exploring ways to establish such collaborations1. Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic made it difficult to make them a reality. From previous examples, we knew that communication through art could improve the quality of life (QOL) for people with dementia. So when I joined the museum in 2021, we first implemented online programs, which were feasible even during the pandemic.

Editorial Team: In 2021, the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum held an online program called the Van Gogh Exhibition at Home for people with dementia and their families, didn’t it?

Fujioka: Yes, it was the first program at the museum specifically for people with dementia. It connected participants with our team of art communicators—called Tobira—and the museum via an online platform, allowing them to view works by Van Gogh and Renoir that were on display at the time. In parallel with the program, the museum sought ways to collaborate with the local welfare and healthcare sectors. To realize this, we hosted a Community Connection Meeting with members from the Taito Council of Social Welfare and people working in medical and caregiving sectors, in the very Art Study Room where we are all now. During this meeting, we introduced the museum’s activities, including the Van Gogh Exhibition at Home program, to representatives from community general support centers, care managers, and the Taito City Office. We later created a video about the program.

Editorial Team: What kind of explanation did you give at the Community Connection Meeting?

Fujioka: We showed footage from the Van Gogh Exhibition at Home program. It helped attendees understand how communication through art and utilizing the museum as a resource could work. At the same time, we recognized that we, as a museum, need to understand local healthcare to collaborate with local communities. It was this realization that led us to visit the Dementia Cafés.

Editorial team: Mr. Nomoto mentioned the Dementia Café earlier. Could you tell us more?

Fujioka: A Dementia Café is a place where people with dementia and their families can get together to share information with local residents and professionals with a view to better understanding each other. According to a 2022 Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare survey there are 8,182 Dementia Cafés operating in 1,563 municipalities nationwide. They are also known as Orange Cafés. We were inspired by these efforts and wondered if we, a museum, could collaborate with them.

Editorial team: What kind of collaboration specifically?

Fujioka: We came up with a plan to invite people with dementia to the museum. When we proposed it at the Community Connection Meeting, attendees expressed interest, saying, “It could provide a different kind of time and experience.” From there, in collaboration with the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum and the Dementia Disease Medical Center of Eiju General Hospital in Taito, we held a program called Orange Café – Exploring the Museum with Tobira: The World of Danish Furniture. Through this experience, we began to understand the significance of holding exhibitions for people with dementia.

Challenges Creating Connections During the Pandemic

Inaniwa: However, during that time, we were still in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, and I imagine there were various hurdles to starting something new from a welfare perspective. What was it like for you?

Chigasaki: Yes, well, the pandemic impacted us heavily. The Social Welfare Council was in a situation where the message was essentially, “Don’t gather, don’t talk, don’t go out.” However, when people, especially the elderly, remain confined to their rooms or facilities, their cognitive functions and walking abilities decline. We had a strong sense of crisis about community activities halting. In the midst of grappling with the question of how people could connect with one another when gathering is prohibited, I still vividly remember the surprise I felt when I saw the Van Gogh Exhibition at Home presented by the team including Mr. Fujioka. I thought, “Even during COVID-19, people can connect and interact like this. That’s the power of art!” (laughs). I was also surprised by the potential of online platforms to draw out emotions, words, and memories from people with dementia, even without face-to-face interaction.

Fujioka: The Van Gogh Exhibition at Home program involved participants engaging in dialogues with our Tobira art communicators. The name Tobira comes from a combination of “Tobi,” short for the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum (Tobi), and the idea of opening a new door, which in Japanese is “tobira.” They are a group of active volunteers, aged 18 and over, from a wide range of backgrounds, who collaborate with curators, university faculty members, and other professionals.

Chigasaki: Watching their activities made me realize how significant the Tobira role is. It’s an incredibly important position. Although I was aware that the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum was recruiting Tobira, I didn’t really know what they did. Despite the physical proximity of being in the same district of Taito, there was a psychological distance from the art world (laughs). While some people visit art museums and galleries in their personal lives, the idea of “connecting with a museum through work or community activities” hadn’t really occurred to us.

Fujioka: Through visiting healthcare and local facilities, I came to realise that every single person working on-site has bright ideas and an interest in trying new things. From a caregiving perspective, creating a safe space in the museum requires more than just our knowledge. However, by combining our respective expertise, I felt we could create something new.

Nomoto: I’ve always had this lingering thought: it would be great if we could connect beyond the walls of the hospital. When we established the connection with Mr. Fujioka and his team, I thought, “Yes, this is it!”

Everyone: (Laughs)

Nomoto: I thought that we could make new activities that support local people with dementia through a collaboration between hospitals and ZUTTOBI. At the same time, I was concerned that people with dementia might experience challenges as they viewed the artworks. I worried that they might experience anxiety in the unfamiliar environment. Despite these concerns, I really wanted to give it a try.

Inaniwa: I often hear that the biggest challenge in collaboration is relationship building. Taking the first step can be one of the hardest parts of a new collaboration and we all know how hard it can be to create something without a precedent. How do you suggest we can overcome this challenge?

Kanahama: I visited “Café YOU” Dementia Café with Mr. Fujioka several times and we realized how enthusiastic the people in charge of the cafe were about creating something with the museum. We joined in with the activities there, playing traditional games and even participating in the same gentle exercises that people with dementia and their families did at the Dementia Café: the simple act of moving our bodies together created a bond, started conversations, and led to us really enjoying ourselves. At that moment, I felt a shared understanding that transcended needs and expertise, and a strong desire to create something together.

Editorial Team: So, you mean that “sharing an experience” is important.

Kanahama: Yes. There were things that I could not have understood without visiting. I’m not from the medical field; my background is in art. Before going, I had a certain amount of concern, wondering how I would fit in at a Dementia Café. But when I went, I felt a deep sense of emotional connection.

Nomoto: At our Taito Hospital, we advocate for a community centred, ‘convivial’ society as part of our management policy. So, I did not have any concerns about connecting with people from different fields. In addition to the Dementia Café, we also hold a “Hospital Festa” in the fall.

Editorial Team: Is the “Hospital Festa” a kind of festival?

Nomoto: That’s right. We open the hospital for a day, host cheerleading performances, give lectures, and enjoy jazz saxophone concerts. We also hold a tour of the operating room.

Inaniwa: You can see the operating room? That really is an open hospital!

Nomoto: Yes. Since we are that kind of hospital, when I suggested the possibility of collaboration with a museum, I was told, “Go for it!”

Continue to Part 2.

- Ms. Inaniwa worked as a chief of Art Communication Team, and curator of Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum from 2011 to 2021. ↩︎