Creative Ageing ZUTTOBI is a project organized and operated by the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum and Tokyo University of the Arts. The term ‘Creative Ageing’ considers what it means to grow older creatively and encourages a positive perspective on aging. The name ZUTTOBI combines ‘Tobi,’ the abbreviation for the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum, with ‘ZUTTO,’ meaning ‘always’ or ‘for life’ in Japanese. The initiative aims to create a society where art and museums remain accessible throughout one’s life. This initiative involves interdisciplinary research and practical applications in collaboration with Tokyo University of the Arts. In this article, we continue the discussion from Part One, exploring insights from four people involved in the ZUTTOBI project.

目次

Orange Café – Exploring the Museum with Tobira: The World of Danish Furniture

Collaboration “Increases Options”

Chigasaki: My current position as a Community Social Worker has a broad scope. Really broad.

Editorial Team: Could you elaborate on the activities you’re involved in?

Chigasaki: Well, the Family Support Center program under the Social Welfare Council focuses specifically on childcare support, which means it cannot address elderly care. Similarly, the Center for the Protection of Rights primarily supports individuals with declining decision-making capacities. However, since the establishment of our department eight years ago, Community Social Workers have functioned as a hub for handling a wide range of consultations from the community. We are essentially open to any kind of inquiry—be it advice for daily life, issues like pigeon droppings, matters related to pets, or even how someone living alone should arrange their end-of-life care. We serve individuals from infants to those over 100 years old, providing a level of flexibility that I think is our key strength.

Inaniwa: I remember you once mentioned how having museum activities integrated into the community gives you “more options,” and that you found this very exciting.

Chigasaki: Absolutely. I think it’s great to have a variety of programs as options. For instance, to improve the quality of life (QOL) for elderly individuals or patients with dementia, we need more than just caregiving or medical services. We should ensure they have as many options available as possible, including experiences that bring joy or a sense of purpose—whether it’s exercise, dance, karaoke, or art. Having art as an additional option is truly valuable.

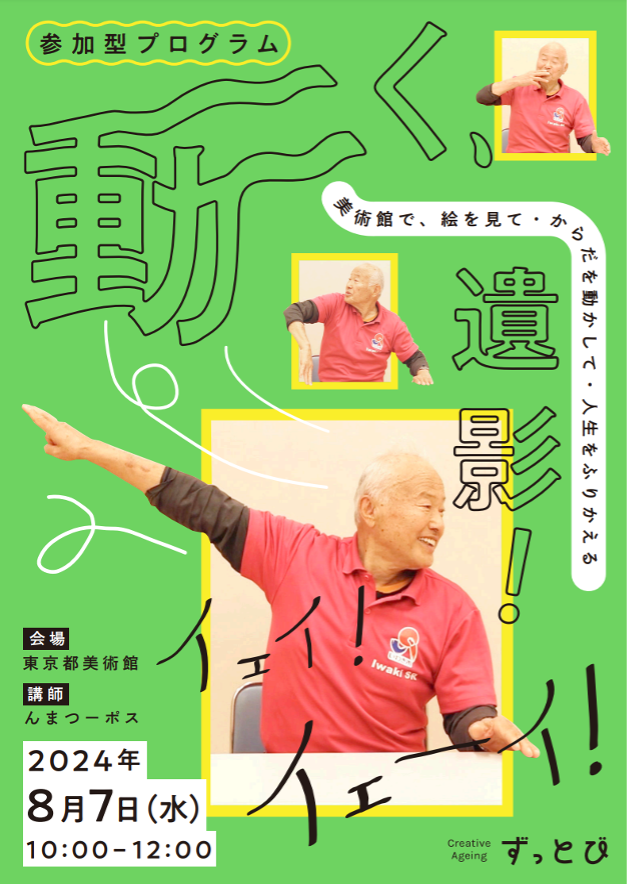

Fujioka: In the summer of 2024, we hosted a program called “Moving Iei (Memorial Portraits)! Yay! Yeah!”11. It was aimed at people 65 and over but anyone interested in gentle activity was welcome to join in. Participants explored the museum with Tobira, viewed artworks, reflected on their lives, and worked with contemporary dance artists to create a piece that captured their movements as a ‘memorial portrait’. It was a bit of a daring program, but a fun one, too! (laughs)

Viewing Artworks with Those Concerned About Dementia

Inaniwa: That sounds enjoyable. What other projects do you have?

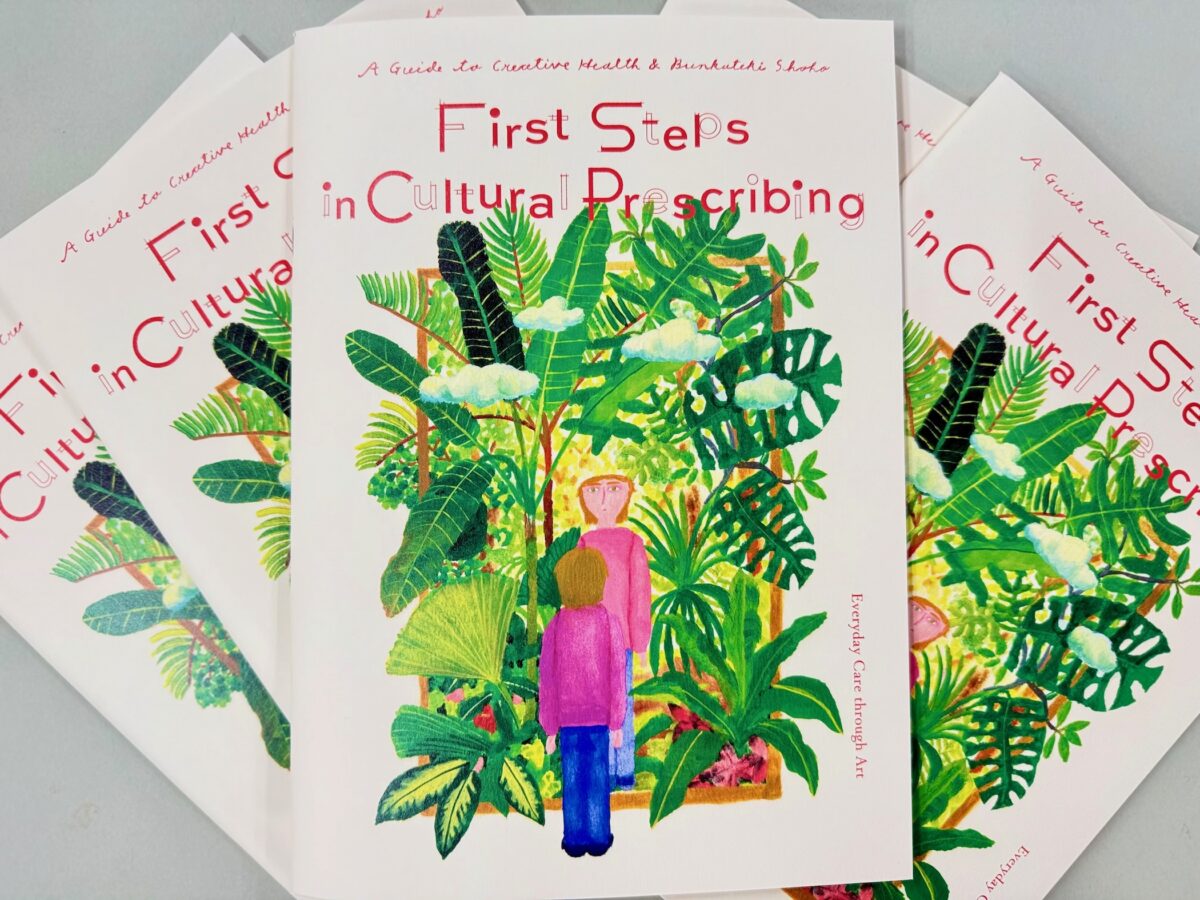

Fujioka: We’re planning to hold another ZUTTOBI Art Appreciation event at the University Art Museum following on from the one we had last year. This program welcomes individuals aged 65 and older who are concerned about dementia, along with their families. We select artworks from the Museum’s collection that are particularly suitable for older audiences or individuals with dementia. Through such initiatives, we aim to spread awareness among healthcare and welfare professionals about how art and culture can contribute to health.

ZUTTOBI Art Appreciation at the University Art Museum, Tokyo University of the Arts in 2023.

Photo by Yusuke Nakajima

Overseas, there are already programs like social prescriptions or museum prescriptions, where hospitals assess patients’ needs and refer them to museums. We hope for more active promotion of such programs by healthcare and welfare institutions, leading to dynamic, two-way communication. As the ZUTTOBI initiative is also a research project2, we have begun more formally examining its social impact and effects on participants. As we evaluate this project, we aim to increase collaborations between welfare, healthcare, and museums both in Japan and internationally.

Kanahama: The Tokyo University of the Arts Museum is very much involved in

ZUTTOBI Art Appreciation. Both the Museum’s Director, Hiroko Kurokawa and University Professor, Hiroshi Kumazawa personally participated in the selection of the artworks.We imagined the viewers as we chose five pieces, discussing things like, “Would clear, bold colors be better?” or “Should we focus on figurative works rather than abstract ones?”

Fujioka: There were no strict selection criteria, but we considered artworks that might evoke childhood memories or inspire storytelling.

Kanahama: That’s right. We looked for elements that would spark engaging discussions. By reviewing the literature about each artwork and selecting pieces suited to the audience, the exhibition became something different from a typical art show. Director Kurokawa was pleased, as this became a new opportunity for the art itself. During last year’s session, sofas and chairs were placed in front of the artworks, creating a relaxed viewing environment. Each group spent about 20 minutes engaging deeply with the artworks, and the conversations were lively.

Orange Café – Exploring the Museum with Tobira: The World of Danish Furniture

Fujioka: In a previous case, as mentioned earlier, we viewed chairs not paintings at “Orange Café – Exploring the Museum with Tobira: The World of Danish Furniture.” Standing before a chair designed by Danish furniture designer Finn Juhl, participants talked about the furniture in their own homes, shared thoughts on what they would like to buy, or even said, “I don’t need any more chairs!” (laughs). There were chairs people could actually sit in, and when participants sat down, medical welfare staff naturally supported them. I was impressed by how naturally they assisted—it was seamless. That kind of response is something we, as art professionals, cannot easily replicate. For every exhibition, we conduct a prior walkthrough of the gallery with healthcare and welfare professionals. They offer insights like, “This area is dark and could be dangerous,” or “This spot might be a tripping hazard.” Their expertise helps shape the program. Collaborating with medical and welfare experts is incredibly reassuring.

Nomoto: That’s true. Healthcare and welfare professionals have the training to understand what to pay attention to and how to act accordingly.

Chigasaki: Even as they chat, they subtly assess each person’s physical abilities. It’s really impressive.

“If you invite me, I’ll feel safe.”

Editorial Team: Even with such interesting initiatives, getting the word out about the program must be difficult. How do you attract participants?

Kanahama: We distribute flyers, but that alone isn’t enough, so we ask healthcare professionals to directly reach out to older adults in the community.

Chigasaki: Community Social Workers build relationships with local seniors. We sometimes take a more direct approach, thinking, “Would this person and their family enjoy this?” (laughs).

Fujioka: It really helps. When Ms. Chigasaki personally hands out flyers, people feel confident and motivated to participate because they trust her recommendation.

Chigasaki: Even if people are interested, a single worry can hold them back. But because of our established relationships, they feel safe: “If you invited me, then it must be a welcoming place.” Of course, flyers help spread awareness too.

Kanahama: There was an event where we struggled to get participants, but when we consulted Ms. Chigasaki, sign-ups came in right away (laughs).

Chigasaki: I spoke to people one by one at that time (laughing). Lots of people hesitate to join without a little encouragement.

Inaniwa: What have you learned from your past activities, and what do you want to focus on in the future?

Nomoto: From my work in clinical settings, I am very aware of how significantly dementia affects families. As a person with dementia gradually loses abilities, how their family perceives and responds to this change greatly impacts the lives of everyone involved. In that sense, we could develop more programs focused on supporting families.

Inaniwa: You mean: care for caregivers?

Nomoto: Exactly. Families play a crucial role. I also think art can provide connections between caregivers. Another point is that most people who visit museums still live at home, but I’d love to bring art experiences to those in hospitals or care facilities. Hospital life can be dull, with few sources of enjoyment. Even just once a month, engaging with art could bring enjoyment and a sense of living your own life.

Chigasaki: I completely agree. There needs to be a support network for family members of dementia patients. Caregivers often struggle in silence. In Japan, the traditional family system still exists, and there’s a strong societal expectation that family members should handle caregiving. This creates pressure, so caregivers need emotional support too.

Editorial Team: It’s clear that support is needed not just for individuals with dementia but also for their families.

Chigasaki: Yes. We also hear more about issues like kodokushi (solitary deaths). More and more people live alone without any relatives or any regular connections with their relatives. We need ways to provide information and encourage them to engage socially. Loneliness isn’t just a problem for the elderly; there are also many hikikomori (socially withdrawn individuals), including young people. Through communication with Tobira, we could offer them not just art appreciation but also communication and a sense of purpose.

Kanahama: For some, it’s not just about looking at art—it’s about having someone by their side to listen. Visiting a museum is an opportunity to dress up and have a change from your usual routine. Families notice this change, and it’s heartwarming to see both participants and their loved ones enjoying the experience.

Editorial Team: It sounds like participants truly enjoy the program.

Kanahama: Yes, they do. Previous participants sometimes come back and do the programs again, which makes me really happy. We want to continue creating programs that people keep returning to. That’s why it’s important to reflect on past experiences and address any issues that arise.

Fujioka: Some active older adults who join our programs go on to apply to become Tobira art communicators. They start as participants, then become engaged with the Tobira Project as partners, expanding the circle of people thinking about aging, loneliness, and social isolation together. We want to keep finding ways to sustain the fun side of this process through our programs.

Inaniwa: There’s still little information on creative health initiatives, and some in the art field might worry that medical professionals won’t take their ideas seriously. That’s why it’s crucial to share the need for these programs, creating a more convivial society and building community connections. Learning from your experiences could inspire more people and regions to join in. Thank you very much for joining us today.

- (This program was scheduled following the interview, on August 7, 2024. The event report is available at the link.):

東京都美術館 Creative Ageing ずっとび 【開催報告】「動く、遺影!イェイ!イェーイ!」 ↩︎ - Creative Ageing ZUTTOBI is one of projects collaborating with the Arts-based Communication Platform for Co-creation to Build a Convivial Society ↩︎